I usually compare the calendering process to rolling out pie dough. In reality, the manufacturing process is a little more complex than that. In the calendering process, PVC material is squeezed between gigantic, heated, polished-steel rollers that form the vinyl into a very thin sheet of film.

A modern calendering line is also more expensive than grandma’s rolling pin, with capital equipment investments ranging typically from $10 million to $15 million. In addition, the calendering rolls alone cost several hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The production lines at companies, such as Achilles, feature advanced computer controls, which allowed continuous monitoring and in-process adjustments of machine functions.

In addition to focusing on the raw materials that create calendered vinyl, I’ll review the calendering process’s basic steps: blending, fluxing, milling, calendering, embossing, cooling and winding.

Raw materials.

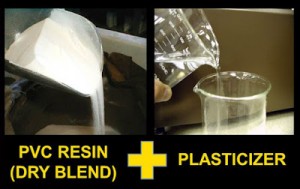

PVC resin is the key ingredient. However, by itself, it’s a very hard and brittle plastic material. Additives — plasticizers, stabilizers, lubricants, pigments and processing aids — change the film’s physical properties and make it easier to process.

PVC resin, pigments and additives comprising the “dry blend” are combined with the liquid plasticizer in a giant mixer. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

Plasticizers, which are liquids incorporated into the formulation, soften the hard PVC resin and make the films more flexible.

Plasticizers in polymeric calendered vinyls are more complex than those in monomeric films. Monomeric plasticizer comprises linear (sometimes branched) molecular chains, whereas polymeric plasticizer features complex branched chains of a higher molecular weight. The weightier polymeric molecules resist migration and create a more stable and longer-life plastic.

Plasticizers add flexibility to the final film. Plasticizer additions soften the film’s feel, or “hand.” Normal vinyl films used in graphics applications contain between 20% and 25% plasticizer. The higher-molecular-weight, polymeric-plasticized mixes have a higher viscosity (rheology) than monomeric systems, and are processed at slower production speeds. These plasticizers are more expensive than the monomerics, and are less efficient, which means they require a higher content of a more expensive material manufactured at lower speeds.

The plasticizer’s molecular weight helps determine its stability. Higher-molecular-weight, polymeric plasticizer comprises very big, bulky, slow-moving molecules. Hence, they stay in the film.

The early, lower-molecular-weight monomeric plasticizer molecules were more mobile. They moved around easily and readily migrated out of the PVC into other adjoining materials, such as the adhesive coated on the film. Modern monomeric plasticizers are less mobile, which limits migration into the adhesive.

Heat and UV light prematurely age products, especially vinyl. As the film ages, it yellows and degrades. Films can lose their elasticity and become brittle. Heat and UV stabilizers slow down this aging process. Although monomeric formulations don’t usually contain UV absorbers, they’re often incorporated into the vinyl (and adhesive) — for overlaminating applications — to impart some UV protection to the digital image or photograph being protected.

Lubricants assist the film’s release from the hot calender rolls during production and act as internal processing aides during production. They not only prevent PVC film from sticking to the rollers, they also improve the compound’s process.

Pigmentation is achieved via inorganic and organic pigments, which are usually first ground into the plasticizer to achieve a specified particle size (for full-color development). The pigment selection will depend upon the vinyl’s end application.

Economical inorganic pigments provide higher opacity than organics. High-performance calendered vinyls use the same pigment opportunities as the more expensive cast products.

The Calendering Process.

By itself, the PVC resin is as hard and brittle as a saltine cracker. Thus, to transform the PVC resin into a flexible plastic, it must be compounded with other vinyl-film ingredients.

The dry blend and plasticizer are combined in a giant mixer. Imagine the margaritas that you could make in blender like this? Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

Once all the raw materials are weighed and blended, into a very fine powder with the consistency of cake flour, the blend is fed into the extruder’s screw — the machine’s fluxing section. Under heat and pressure, the extruder continues the mixing process, evenly dispersing all the additives with the PVC resin. In the fluxing or plastification process, all the separate ingredients fuse together into one homogenous mass of plastic called the “melt.” As the fine powder melts, at approximately 300°F, the extruder kneads the material into a hot, twisted plastic rope. The extruder also helps strain out any foreign particles, which could damage the machinery.

In the extruder the ingredients are heated and fused together in what is called the plastification process. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

Next, the hot, plastic rope is fed into a two-roll mill bin and rolled into a rough sheet of film. In the manufacturing process, the heat is continually increased, making the film more malleable so it can be rolled increasingly thinner. During this milling process, edge trim can be reworked into the mix.

In the two-roll mill the hot plastic rope is squeezed into a thick, rough sheet of plastic. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

After the two-roll mill, the material passes a metal detector. This inspection step prevents any metal from reaching the calendering rolls. Even the tiniest metallic speck could cause irreparable damage and necessitate roller replacement.

Calender Rolls.

The calender comprises four, rather heavy, highly polished, 2-ft.-diameter steel rolls. Calendering rolls can be arranged into various configurations, such as “L,” “F” (or inverted “L”) and “Z”. The plant I visited utilized a four-roll “L” configuration.

The thick sheet of plastic is fed into the top of the calendering stack. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc

During the calendering process, the heat increases, and the vinyl sheet passes between the rollers. During this process, the film is squeezed into a much thinner and wider sheet.

The calender rolls subject the vinyl sheet to thousands of pounds of pressure per square inch. Such intense forces and rapid production speeds can bend and deflect these massive rolls.

To compensate for the rolls’ deflection, some complex mechanical-engineering ideas have been incorporated into modern machinery, including crowned rolls (which are thicker in the middle than on the edges) and rolls that are crossed slightly to one another, rather than perfectly parallel, and designed to counter the rolls’ bending by applying pressure in the counter-direction.

In the calendering stack the plastic film is squeezed into a much thinner and wider sheet. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

These measures ensure an optimum profile so the vinyl’s caliper remains uniform. After the web travels through the production line’s calender section, the strip-off, or pick-off roll, strips the sheet from the calendering rolls.

To impart the film’s surface finish, the sheet goes through an embossing unit. Here, the film is pressed onto an embossing cylinder with a matte-rubber pressure cylinder. The resultant surface finish depends upon this embossing cylinder’s condition. A high-gloss surface is achieved from a highly polished chrome cylinder, whereas a matte surface is achieved from a matte-engraved emboss cylinder. The film’s reverse side has an unspecified matte surface.

After the sheet is calendered, it is passed through a series of rollers, which impart a surface finish. In this manufacturing stage, the thickness of the sheet is measured continually across the web to ensure product consistency. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

As the vinyl sheet passes over and under a series of chilling rolls in the cooling section, the vinyl quickly cools. The cooling process anneals the vinyl into its final form.

The vinyl film is then wound, using highly sophisticated, progressive-tension winders, to minimize any tension that could result in future, dimensional-stability issues. For high-gloss films with a soft hand, it’s important to keep roll lengths to a minimum, with controlled winding tension, to reduce the tendency for gloss reduction through the roll. This reduction is caused by “cold embossing” — the matte reverse side presses onto the roll’s high-gloss surface. This is temporary “damage,” and the gloss can easily be refreshed with heat during subsequent processing.

After the film is wound into a master roll, it is shipped to an adhesive coater, such as RTape. Photo courtesy of Achilles USA, Inc.

Although the facestock is a vinyl film’s key ingredient, it’s only one ingredient in the pressure-sensitive sandwich. How a film cuts, weeds and handles depends on how all the components work together. Two rolls of the same facestock, coated with different adhesives, will likely perform differently. Remember this why it is important that you evaluate each new vinyl film product.

As seen on hingstssignpost.blogspot.com